Carl Tuggle, World War II veteran, civil rights pioneer, and survivor of the Port Chicago disaster, died on December 29, 2022 in Forest Park, Ohio. Tuggle was the last known surviving sailor of the 1944 Port Chicago disaster.

Born on January 24, 1925 in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Carl and Blanche Tuggle, he was the third of four siblings — Ralph, Frederick, and George Tuggle — who all preceded him in death.

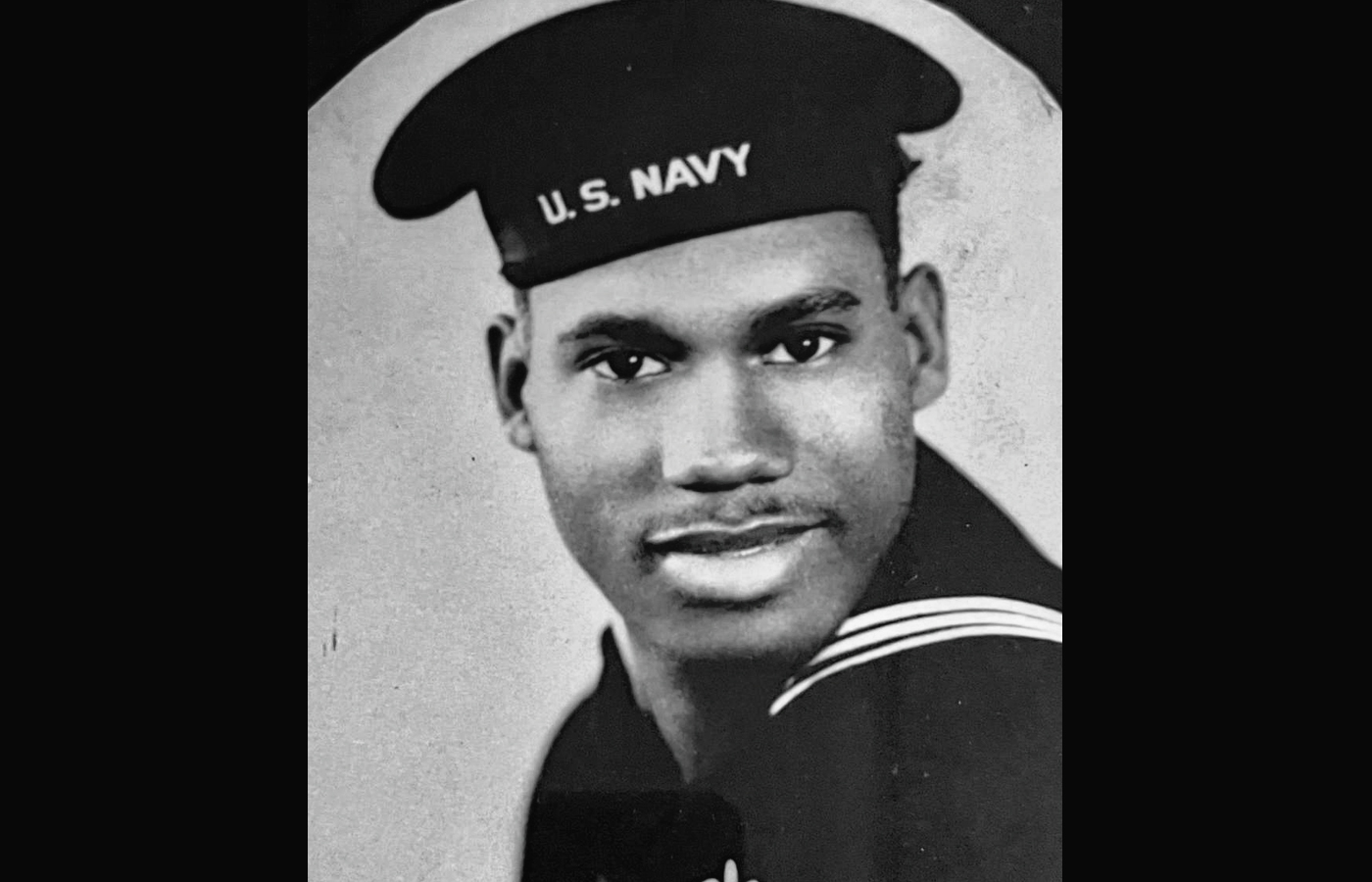

In 1943, after graduating from high school, Tuggle was drafted into the Navy at age 18. In basic training he passed the skills test and wanted to become an aviation mechanic but instead was sent to Port Chicago Naval Magazine to load hazardous explosives onto ships. As the Naval Magazine was enforcing Jim Crow segregation and only Black sailors were loading explosives, he and the other Black American sailors realized there would be no opportunities for advancement or even equal treatment as their White counterparts:

"After we were there for about 4 to 5 months, we thought we should have some opportunity to have increase in rank, have some type of training, or get some type of leave. We were denied all three," recalled Tuggle. [1] "It was a thing that caused frustration among us because they weren't treating us the way we was supposed to be treated." [2]

In interviews, Tuggle recalled July 17, 1944, the night of the Port Chicago disaster:

-

"I got thrown off my bunk and I got scars on my hand from glass. [2].

We heard the explosion and without a second thought we knew exactly what it was because when we first got to Port Chicago, we went up to the docks, because we had fear of explosion, and those who had been there before we arrived said, 'If there ever was an explosion, you wouldn’t know anything about it.' [1]

The day after the disaster, Tuggle and other survivors were bussed to Oakland Naval Base:

- "They offered us the opportunity to go back [to Port Chicago] and get our belongings. I told them they could have it. I didn’t want to go back to that place." [3]

Tuggle had about a week at the Oakland Naval Base before he was sent back to work. "After the explosion they gave them [White officers] all [30-days] leave. Every officer got leave on that base, but they denied each one of us [Black sailors] leave. They didn’t allow any of us to go and see our families. If you have a tragic accident happen at school or anywhere they have someone commence counseling to try to talk to them. But after that week they wanted us to go back to loading ammunition."

Tuggle recalled the famous work stoppage at Mare Island, where 258 Black sailors refused to return to loading munitions until they received fair treatment and improvements to working conditions:

- “They called us out to fall out in formation which we generally do before each working period. They asked us if we’re going to work and we said, 'Sure, we’re going to work.' So we were out in line and they said, 'Fall in, fall out, and go up to the dock to the areas where ships were to be loaded.' Didn’t no one move... The officers in charge of our division came to our leader and asked him to have the boys fall out and we didn’t fall out. So they came around and said, 'Are you going to work?' and didn’t no one say nothing and didn’t no one respond.” [1]

Tuggle and the other sailors were then placed in captivity on a barge with Marines standing guard. As Tuggle recalled, the next day the sailors were marched outside:

-

"We stood there at attention for about ten to fifteen minutes and then all of a sudden here comes an automobile with an American flag and Naval flag on it and it was the Commander of the Twelfth Naval District. We didn’t know who it was. So he marched around and asked each individual who was standing there and asked them 'Are you going to work?' and I said, 'Yes, I’m going to work but I’m not going to load no ammunition.' ” [1]

"They took us back to that barge and locked us down... Didn’t no one refuse to follow an order, because we were never given an order to go to work. There was a question asked of us. He said, 'Are you going to work?'. He asked us a question, he didn’t give us no order to go to work. And there is a big difference there." [1]

As Tuggle recalled, many of the 258 sailors who initially refused to load munitions went back to work, but others, like Tuggle, were locked in a brig for over three months without explanation:

-

"The statement they gave us for why we were locked in the brig was 'for safe keeping.’ After we were released from the brig, we were taken to the docks, put aboard a ship, and shipped overseas with no orders and no direction to where we were going. We ended up in New Caledonia down there near Australia." [1]

"I had a friend that I grew up with who was stationed at New Caledonia at the time. I hitched a ride on a truck and went to the base where he was, and guess what they were doing? Unloading ammunition." [1]

Looking back at his time in the Navy, Tuggle considered it a "gap" in his life:

- “I was raised to believe you can do anything you want if you put your mind to it and provide the skill, but I was seeing the opposite picture of that when I was being exposed to the things that the Navy was trying to do... My personal opinion of the place is it was one of the worst places I ever been in my life. I consider the time I spent in the Navy was three years of my life wasted. Because when you try to do something to better yourself and you run into a brick wall, and you know that you had been told before you got to that wall that you can go around that wall, but they don’t let you go around it. And that’s what happened to me.” [1]

After finishing his time in the Navy, Tuggle continued his education at The College at Wilberforce (Central State University), graduating in 1950 with a Bachelor of Education degree. It was there he met the love of his life, Elizabeth (Betty) Jane Tuggle, whom he would remain married to for 64 years.

Following college, he continued his education earning a Master of Education degree in 1952 from Columbia University in New York City. He also completed some post graduate studies at the University of Cincinnati and Xavier University. He began his teaching career in 1952 at Hubbard High School in Sedalia, Missouri teaching physical education & coaching basketball and football. His long career with the Cincinnati Public School System started in 1954 and he retired in 1990. Despite his extensive education and qualifications, Tuggle had times in his life when he was denied opportunities to teach and was once told he had "too much education." [1]

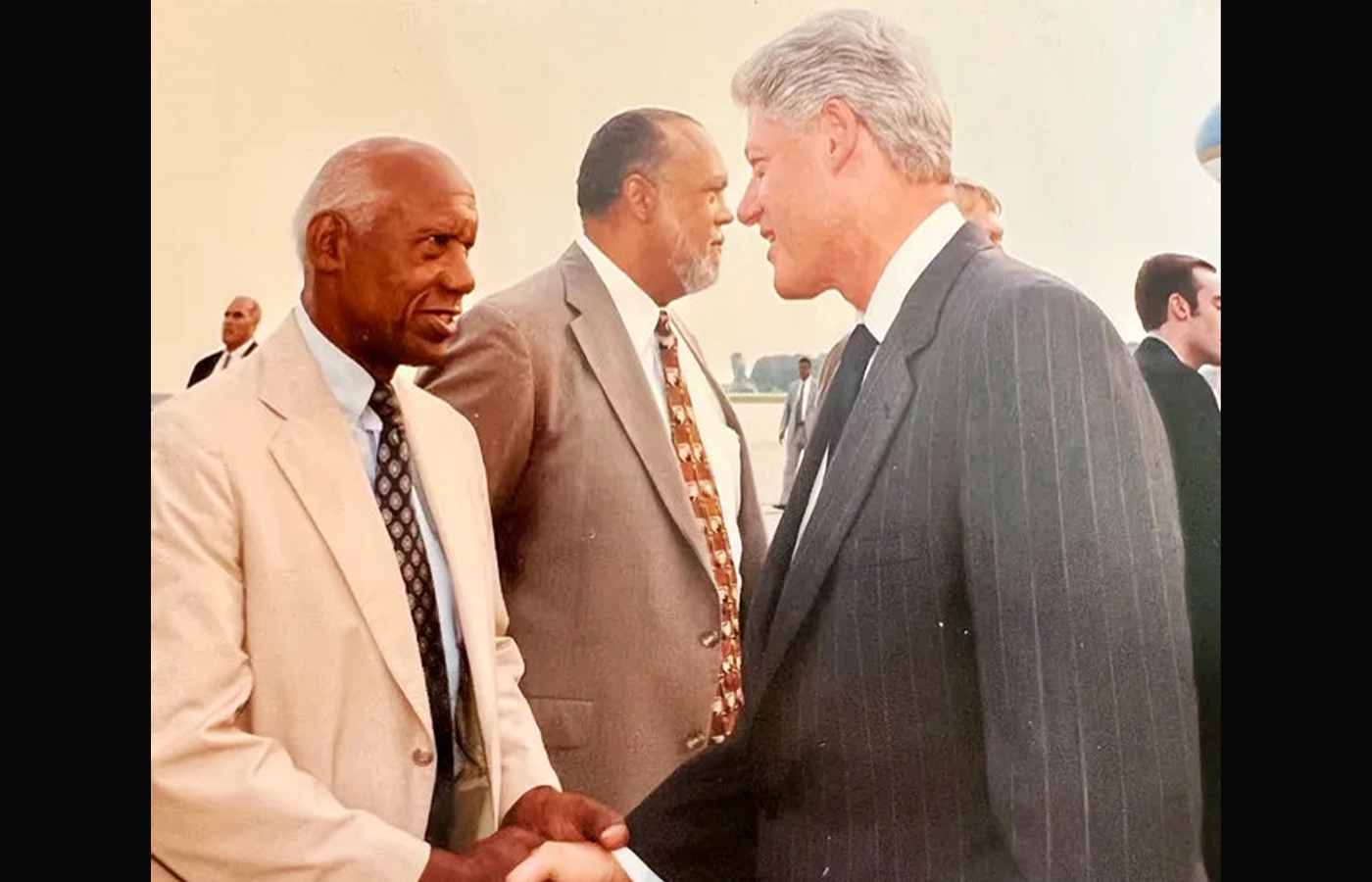

Later in life, Tuggle continued to advocate for the sailors of Port Chicago, traveling several times to California and Washington DC to try to clear the records of the sailors. He wrote letters and made calls to members of Congress, Presidents and the U.S. Navy asking them to recognize the discrimination Black enlisted men faced during World War II and particularly in Port Chicago:

- “There should be an apology. Our records should be expunged. They got on [my record] that I was given a summary court martial and fined but I’ve never been before an official body that says you’re being court-martialed. It’s on my record." [1]

As for his feelings about the work stoppage and wrongful convictions, Tuggle said the Navy "ran into a group of men who were doing things right and who were challenging them. That’s what they couldn’t handle." [3]

Carl Tuggle was 97 years old when he died. He is survived by three daughters, Dr. Blayre Rebecca Tuggle, Charlette DeShane (James) Fuller, and Carlotta Elizabeth (dec. Fred) Jackson. Three grandchildren, Ashtyn Leigh Fuller, Justin Carl Fuller and Alanna Patricia Jackson. He also leaves his beloved niece Beverly (Clarkley, Sr.) Powell, who was like a daughter to Carl & Betty. Carl will be lovingly remembered by his many nieces and nephews, cousins, godchildren, a host of extended family members along with countless lifelong friends and neighbors.

Carl Tuggle and all who served at Port Chicago will not be forgotten, and Carl's story will live on through memories shared, as well as education about his integrity and bravery in standing up and speaking out against injustice and racial inequality in the Navy. ⋆

[1] Cincinnati Public Library: https://digital.cincinnatilibrary.org

[2] Dohn Panther Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wWU8oau9PKI

[3] Los Angeles Times: https://www.latimes.com/archives

Obituary: https://thompsonhalljordan.com/obituary/carl-tuggle/